Learning Rust: Download and deserialize 10 000 files in 9.833 seconds

TL;DR: CODE; I built a Rust app that downloads and processes 10,000 CSV files from S3 in ~10 seconds using async concurrency with semaphores … all running on a single thread.

As I was getting ready for an upcoming AWS re:Invent 2025 talk, I wanted to show how you can use Rust’s fearless concurrency with AWS and get some fantastic performance out of it. Oh, all that with a single thread! Let’s look at how I processed 10K CSV files from Amazon S3 in 10 seconds.

My goal here is nothing fancy, I want to load all the data from an S3 bucket, deserialize it into a Rust struct, and (in the future) do some processing and store it in Amazon DynamoDB.

First off, let’s see what am I dealing with here. I’ve generated a bunch of dummy CSV files that look like so:

timestamp,temp,humidity,measure_point

2025-11-26 02:56:13 UTC,19.8,59.1,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:20 UTC,22.4,58.2,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:27 UTC,21.9,60.0,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:34 UTC,23.1,63.8,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:41 UTC,20.3,62.9,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:48 UTC,23.3,63.2,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:56:55 UTC,22.5,63.4,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:01 UTC,23.7,67.7,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:08 UTC,21.9,65.3,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:14 UTC,21.7,65.7,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:21 UTC,21.2,60.9,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:27 UTC,20.8,63.5,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:33 UTC,20.3,62.8,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:38 UTC,21.0,60.1,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:44 UTC,20.2,58.9,Kyiv_18

2025-11-26 02:57:48 UTC,22.1,59.6,Kyiv_18

[...]This data is meant to represent data collected by temperature sensors spread across Eastern Europe. And it contains 4 columns timestamp, temp, humidity, and measure_point. And each CSV file has only 100 rows, which means we are not dealing with huge amounts of data.

This data was actually generated by another simple Rust application, and then uploaded to a normal S3 bucket under a single data/ prefix. Hence I did not truly optimize my data storage for performance, but that is okay in this example, as my bottleneck will be my network speed. (** shakes fist at public wifi **).

☝️ Tip:

To upload vast sums of files to Amazon S3 make sure to set up

max_concurrent_requestsanduse_accelerated_endpointin your AWS CLI configuration. This has the potential to speed up data transfer into your bucket. For the upload itself the fastest way to point theaws s3 synccommand at a directory where your data is:

aws s3 sync ~/my_data s3://bucket-name/prefix

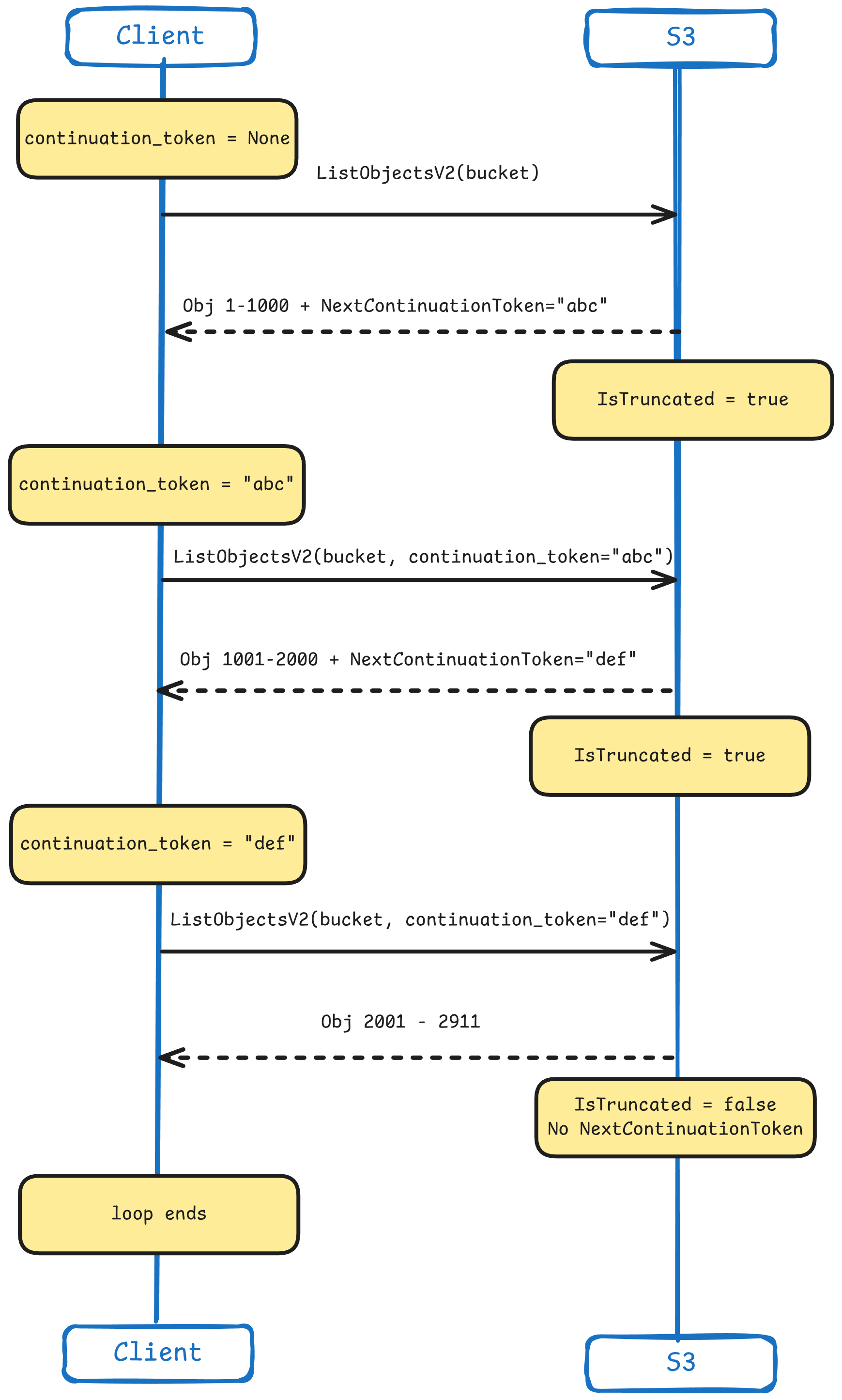

To start off, let’s create a function that will list all the .csv files inside of a bucket. In this function we will be using something called a ContinuationToken from the AWS S3 API. This is used for pagination when making the ListObjectsV2 API call. By default this API call will return only 1000 keys (objects), and if there are more it will also include the IsTruncated: true and a NextContinuationToken. This indicates that there are more keys available.

When we initialize this function, we set the continuation_token to None, and during every call in the loop we sent it back with the request if it exists. Once the token no longer exists, we consider all the keys listed and there are no further pages.

Here is how it looks on a sequence diagram:

The rest of the code is rather simple, as it is just calling the ListObjectsV2 API on a specific bucket at a specific prefix. However we are doing some iteration on specific file extensions (.csv duh).

This bit specifically:

if let Some(contents) = response.contents {

objects.extend( // Extend the vector with the contents of the iterator

contents.into_iter()

.filter_map(|obj| { // Creates an iterator with both a filter and a map

obj.key()

.filter(|key| key.ends_with(".csv")) // Filter out .csv files

.map(|key| key.to_string()) // Convert them all to String

})

);

}We are looking into the .contents of the response we got. And if it exists we extend the objects vector with a filtered list of keys. Oh and since the filter would return a &str we are just converting it into a String as that is what our function needs to return.

Lastly, once we break out of the loop we return a Ok(objects). Now, on to the main event - the processing 👏

Here is the full function now that we are done with it:

async fn list_all_csv_objects(s3: &Client, bucket: &str, prefix: &str) -> Result<Vec<String>, anyhow::Error> {

let mut objects = Vec::new();

let mut continuation_token = None; // Initialize the token as None

loop {

let mut request = s3.list_objects_v2()

.bucket(bucket)

.prefix(prefix)

.max_keys(1000);

if let Some(token) = continuation_token { // If the token is not None

request = request.continuation_token(token) // Append the continuation_token to the request

}

// Make that call

let response = request.send().await?;

if let Some(contents) = response.contents {

objects.extend(

contents.into_iter()

.filter_map(|obj| {

obj.key()

.filter(|key| key.ends_with(".csv"))

.map(|key| key.to_string())

})

);

}

// get the next_continuation_token from the response

continuation_token = response.next_continuation_token;

// If its None, this is our last loop

if continuation_token.is_none() {

break;

}

}

Ok(objects)

}Here is where the magic happens. I’ll be using streams, semaphores and deserialization to get our data from the S3 bucket onto my Structs. In the previous function we didn’t actually download any files, just listed them. In the next function we will download them all as fast as possible.

Before I move on, look at this code:

async fn process_csv_parallel(s3: &Client, bucket: &str, csv_keys: Vec<String>) -> Result<Vec<Record>, anyhow::Error> {

// NOTE:

// Not using multi-threading here as the bottleneck is IO not CPU

// Limit concurrent downloads to 750 - this is 750 S3 API calls (to avoid throttling)

let download_semaphore = Arc::new(Semaphore::new(750));

// Convert Vec<String> into a stream for paraller processing

let results: Result<Vec<Vec<Record>>, anyhow::Error> = stream::iter(csv_keys)

.map(|key| {

// Bunch of cloning

let s3 = s3.clone();

let bucket = bucket.to_string();

let sem = download_semaphore.clone();

// Return async closure for each async task (each key in this case)

async move {

// Get the semaphore permit (blocks if 50 downloads are already running)

let permit = sem.acquire().await?;

// Download CSV

let response = s3.get_object()

.bucket(&bucket)

.key(&key)

.send()

.await?;

// Collect response body and convert to UTF-8

let body = response.body.collect().await?;

// We are done with the API, drop the permit

drop(permit);

let csv_content = String::from_utf8(body.to_vec())?;

// Parse CSV in Memory into the Record struct

let mut reader = csv::Reader::from_reader(csv_content.as_bytes());

let records: Result<Vec<Record>, _> = reader

.deserialize() // Convert each CSV row to Record

.collect(); // Collect all rows

Ok(records?)

}

})

.buffer_unordered(1000) // Run up to 1000 async tasks concurrently (task scheduling)

.try_collect() // Collect all results, die on first error

.await;

// Flatten Vec<Vec<Record>> into Vec<Record>

Ok(results?.into_iter().flatten().collect())

}Nice …

Let’s talk about semaphores. A semaphore (also a word for traffic light in my native language - semafor) is a concurrency control mechanism that limits how many tasks can access a resource simultaneously. Imagine it a permit system, with a fix number of permits given out to tasks, that then later return that permit and make it available for other to take over.

Think of it like a parking garage with a limited amount of parking slots, and new cars can only come in once the slots free up. Well, with semaphores you define how many slots you have, and how to give out parking permits.

In our function we are using a semaphore from tokio and placing it inside of an Atomic Reference Counter or Arc as we want to share the semaphore between different asynchronous tasks.

let download_semaphore = Arc::new(Semaphore::new(500));But then … Why are we cloning the semaphore with download_semaphore.clone(); ? Well that’s the neat part … We’re not! Cloning an Arc is very special, and very cheap.

When running an Arc::clone(), we are actually 1/ Creating a pointer to same heap data; 2/ Atomically increasing the reference number; and 3/ We DO NOT actually copy the underlying data. 👏 Speed!

Every time we clone, we are just incrementing the reference counter and pointing to the same part of the heap. Each time clone is dropped, the reference counter goes down. Once it reaches 0, the heap is deallocated. This is a big deal in Rusts automatic memory management.

Okay, back to the code.

We are now kicking off our async move magic here. This is creating a task for each key (object/csv file) we process. This task then acquires a permit from the semaphore, if there is no permits it will wait for one to be available.

Then some pretty standard things happen, we make the get_object() API call to S3 for a specific key. This downloads the actual object and makes it available for us to process. And “the processing” in our case is just deserializing it into its own Object, or Struct.

Btw, here is how I organized the struct for the CSV data, and yeah I know, I should have used something other than String. But maybe you can correct me in the comments 😉.

#[derive(Deserialize)]

struct Record {

timestamp: String,

temp: String,

humidity: String,

measure_point: String,

}The deserialization is happening with the csv crate, and it’s .deserialize() method. Btw, the reason let result has a type definition of Result<Vec<Record>,_> is because the .deserialize() method actually can fail, so it returns an iterator where each item is Result<Record, Error>. Then we just .collect() them all into our desired return type.

Lastly we return an Ok(result?) - the reason we are propagating the error with ? is because we want to fail if any of the tasks fail. Our killswitch is the .try_collect() method down the line. Let’s talk about that part now.

We have another way to manage limits.

If you look closely at the code I shared above, you will find another way I am controlling concurrency and limits:

// Convert Vec<String> into a stream for paraller processing

let results: Result<Vec<Vec<Record>>, anyhow::Error> = stream::iter(csv_keys)

.map(|key| {

let s3 = s3.clone();

let bucket = bucket.to_string();

let sem = download_semaphore.clone();

async move {

// [...]

let permit = sem.acquire().await?;

// Download files

// [...]

drop(permit);

// Process files

// [...]

}

})

.buffer_unordered(1000) // Run up to 1000 async tasks concurrently (task scheduling)

.try_collect() // Collect all results, die on first error

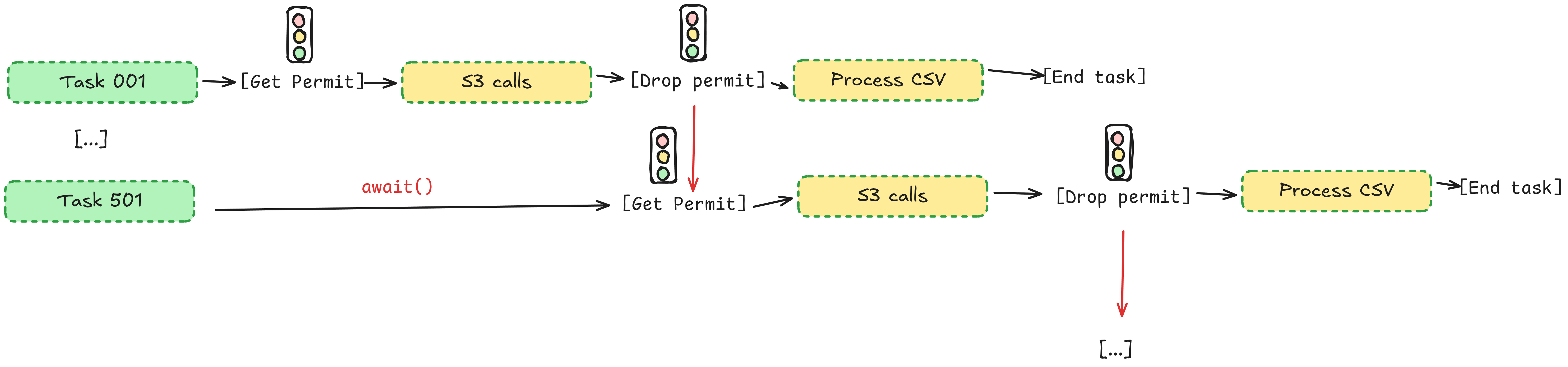

.await;That .buffer_unordered(1000) controls the task scheduling. Namely in this scenario I can only schedule up to 1000 concurrent tasks. But wait, you say, isn’t this what semaphores are for? Yes, but in this case we are combining the two things for better resource management.

You may notice a little drop(permit); in our code after we are done with the S3 APIs. This means we are explicitly returning back the permit we got from the semaphore and that frees up another task to work.

But why? Well, let me explain what we have here:

What is happening here, because certain parts of our work are a bit more prone to throttling (the API calls to S3), we use the semaphore to limit the amount of concurrent executions of that. First off, the task buffer starts 1000 tasks, but only 500 of those can actually start with the S3 APIs (they all do the cloning part at the same time), then as tasks finish with their S3 API calls and drop() the semaphore permit they got, new tasks start running those S3 API calls. Look at this thing I’ve drawn… maybe this makes more sense:

It’s an excellent way to manage certain parts of an concurrent system. In our case it does not really matter that much because most of our bottleneck is the S3 API, but say our CSV processing took way longer. This way we could have a bunch of S3 files downloaded and queued up ready to go while we wait for the tasks that are currently processing to finish.

I do ask you dear reader to look more into this topic, and see how you can further optimize your Rust applications.

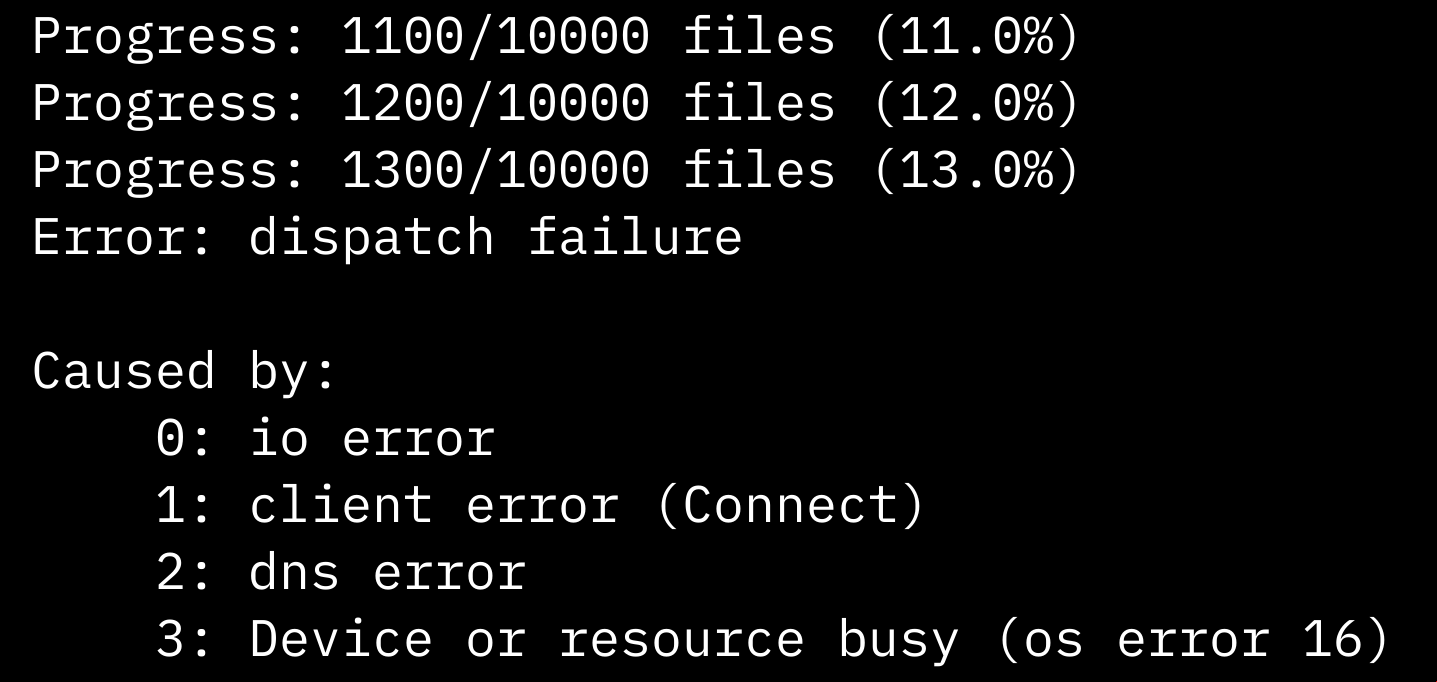

Okay, ready, set, go! 🚀

Wow, 9.833 seconds to download and process 10 000 CSV files using public wifi in a coffee show. Impressive.

☝️ Tip:

I am using just as my command runner here. So when I ran

just benchmarkI actually ran the following command:

time RUST_LOG=error cargo run --release

Now, this is not the end. I am looking to see how far I can push this by doing a few things:

You can find the complete version of my main.rs here: Gist

Rustaceans are very proud to shout from the rooftops how Rust has fearless concurrency. While this example shows parts of it, that is how you can manage your tasks and use semaphores. There is so much to learn and experiment with.

So, the question is: When to use this kind of pattern? Well, it depends. But this kind of pattern async + semaphore pattern works well with workloads that hit IO Limits, work with rate limited APIs, and execute a lot of small tasks. So stuff as batch processing a lot of files from some cloud storage, web scraping (don’t do that), bulk API operations, log processing… But do tell me, where do you see this as working really well.

I am quite impressed with how much of a beating Amazon S3 can take, but I do need to implement some sort of throttling detection/retry mechanisms, as if I would push my semaphore numbers too high I would get bottlenecked somewhere (looking at you crappy coffee shop wifi 👀).

Thank you so much for sticking around this much. See you in the next one ✌